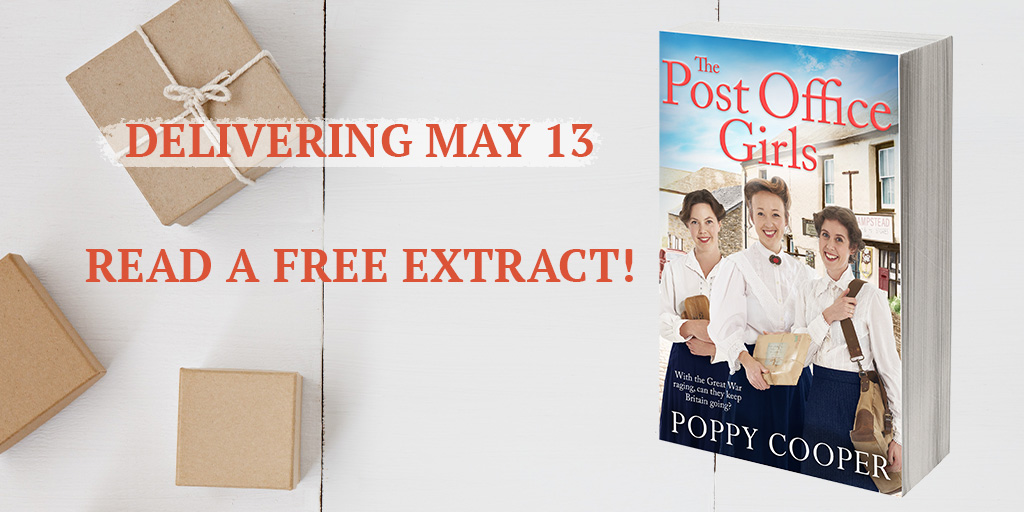

Free Extract: The Post Office Girls by Poppy Cooper

With the Great War raging, can they keep Britain going?

1915. On Beth Healey’s eighteenth birthday, she hopes that she will be able to forget the ghastly war and celebrate. But that evening, her twin brother Ned announces that he has signed up to fight.

No longer able to stand working in her parents’ village shop while others are doing their bit, Beth applies to join the Army Post Office’s new Home Depot on the Regent’s Park, and is astounded to be accepted. She will be responsible for making sure that letters and parcels get through to the troops on the front line.

Beth is thrilled to be a crucial part of the war effort and soon makes friends with fellow post girls Milly and Nora, and meets the handsome James. But just as she begins to feel that her life has finally begun, everything starts falling apart, with devastating consequences for Beth and perhaps even the outcome of the war itself. Can Beth and her new friends keep it all together and find happiness at last?

Prologue

October 1915

Beth stood very still and the world stopped with her, grinding to a halt while she decided what to do next. She had a choice.

A stark choice.

And what she did next mattered. Really mattered. Mattered more than anything that had ever happened to her. Indeed, it mattered more than anything that would happen in many people’s lives – even if they lived to be one hundred years old.

If she ran for help, an innocent person would die. And they were innocent; in spite of everything, deep down she was absolutely sure of that. They might have made mistakes, huge mistakes, they might have teetered on the edge of disaster but, at the end of the day, they were innocent and as much a victim of the war as if they had been fighting at the front.

But if she stayed and tried to save them there would be devastation and loss beyond measure – it might even affect the outcome of the war.

So, what to do?

One special person versus the greater good.

The greater good versus one person.

A crash, a moan, and the world started to speed up at the very instant Beth leapt into action.

At the end of the day, she knew – had always known – exactly what she needed to do.

I

April 1915

Woodhampstead, Hertfordshire

I’m eighteen years old today.

The words beat like the clatter of hooves on cobbles through Beth’s head, tightening across her skull, making her temples throb.

I’m doing nothing to help.

These words were higher, shriller, like a knife dropped onto a plate. They made Beth’s breath catch and her hands shake – almost as though they belonged to someone else . . .

‘That’s under, Elizabeth.’ Mrs McBride’s voice was sharp. ‘Don’t you dare be tricky with the butter – not today, not ever. There’s a war on, don’t you know!’

‘No, Mrs McBride. I mean, yes, Mrs McBride.’

Sweat prickled the roots of Beth’s plait under her neat, white cap. Nerves. Indignation. She was never tricky with the butter. She was never tricky with anything. It wasn’t in her nature and, anyway, Ma would have something to say if she tried. Ma loved a quote, especially from Queen Victoria, and ‘honesty guides good people’ was one of her favourites.

The family shop – J.A. Healey, General Provisions of Woodhampstead – was built on honesty. Everyone knew that. It was what kept customers coming back. Well, that and the fact that there weren’t any other grocers in Woodhampstead.

Mrs McBride was right, though. The piece of butter Beth had taken off the main block was well under half a pound. There was an art to cutting it and Beth was usually pretty accurate – better than Sally, better even than Ma – but today her eye was out. Biting her lip, she added more with the wooden pats. It took several attempts, but finally the scales were balanced and she smacked the misshapen lump into a smooth, neat rectangle. And, all the time, Mrs McBride kept talking. About how the war was dragging on and the casualties were mounting. The new front opening up in the Dardanelles – wherever that was.The dreadful use of poison gas by the enemy. And how it was probably a good thing that Beth didn’t have a sweetheart away at the front because, well, no one knew what the future held, did they, dear? On and on she droned, until Beth felt like screaming – do you think I don’t know? – but she kept her head carefully down while she wrapped the butter in a square of waxed paper and tucked the edges under, just so.

She wondered if she should interrupt and tell Mrs McBride that today was her eighteenth birthday. But no, there was no point. The old lady wouldn’t care – after all, Beth was neither coming of age nor coming out – and it might just prompt a whole load of extra questions about what her twin brother Ned was going to do next.

It was only when she had quite finished wrapping the butter that she allowed herself to look up. ‘Will there be anything else?’ she asked with a polite smile, putting the butter into Mrs McBride’s basket and entering the purchase into the ledger in her small neat hand.

‘I don’t think so.’ Mrs McBride didn’t move. ‘Although the butter’s not too salt, is it, dear? I’m making lemon curd to send out to my great-nephews at the front.’

Really?

After the butter had been weighed and wrapped?

The war is raging and I’m discussing lemon curd with Mrs McBride.

‘I tried it this morning and I think you’ll find it isn’t salt at all,’ said Beth calmly. ‘But if you’d like a taste for yourself . . .’

I’m doing nothing to help.

Without waiting for an answer, Beth pared off a small sliver and put the little curl on a scrap of paper. Mrs McBride sampled it leisurely. Eventually, she smacked her lips and pronounced it just the right side of acceptable. Then she picked up her basket, nodded to the other shopper and swept out into the rain. As the doorbell clanged, Beth allowed herself the luxury of a tiny sigh of relief.

‘Coo, she doesn’t half go on, does she?’ giggled the next customer as Mrs McBride’s ample back view disappeared up the street. It was Florence Emmett, a pretty red-headed acquaintance of Beth’s from school. Florence worked in the kitchens at Maitland Hall, the mansion on the outskirts of the village where Beth’s brother, Ned, was a gardener. Florence rarely came into the shop – in fact, Beth had barely seen her for months – but now here she was, putting a couple of baskets onto the counter and tucking a stray Titian- coloured curl behind her ears.

‘She’s lonely,’ said Beth diplomatically. She could think of various other – and possibly more apt – words to describe Mrs McBride, but Ma took a dim view of gossiping in the shop, and especially about the customers.

Florence shrugged. ‘There’s a lot of people lonely nowadays,’ she said dismissively, ‘and most can keep a civil tongue in their head. Anyway, never mind her. Cook’s sent me in because she needs a few sundry items. Although she was gabbling that fast, I’ll be blowed if I can remember the half of it. There’ll be hell to pay if I forget something. We definitely need tea. And sugar . . .’ She trailed off, rosebud mouth pinched and worried.

Beth smiled reassuringly. ‘Didn’t Cook write down what she wanted?’ she said. ‘Ivy usually brings in a list.’

‘I’ve got a list,’ said Florence, ‘but Cook’s writing looks like a couple of spiders have been at the sherry.’

Beth laughed. ‘Shall I have a go?’ she suggested, holding out her hand. She was used to deciphering even the densest of scrawls. Four years of working in the shop and seeing to all manner of shopping lists had seen to that.

Florence handed over a torn-off piece of paper and Beth scanned the list. Cook’s writing was difficult at the best of times, but today it was even worse than usual. It didn’t help that the list had got wet in the rain, which had made some of the letters run.

‘What happened here?’ Beth asked in amusement.

‘Cook couldn’t find her specs,’ said Florence.

Squinting at the letters, it didn’t take Beth long to confirm that Cook needed tea and sugar – rather a lot of each and maybe more than their depleted stocks could supply – as well as flour, coffee and a variety of packets and tins. Soon Beth was scurrying around the shop, climbing up the ladders to get things from the top shelf, weighing and measuring, gradually assembling the order.

‘Why’s Cook sent you today?’ asked Beth, stacking the last tins of crab onto the counter. ‘Where’s Ivy?’

‘Gone.’

‘Gone?’ echoed Beth, bemused. Surely, steady, sensible Ivy hadn’t got herself into trouble? ‘Gone where?’

‘Gone to “do her bit”,’ said Florence, mimicking Ivy’s distinctively high voice. ‘She just upped and offed without so much as a by your leave. Cook was not happy. None of them were.’

Beth stared. Girls didn’t just leave. They stayed where they were – where they’d been put, to be more precise – until they got married. And then they left to look after their husband and to have babies. It was just the way things were. It was the way things had always been, like it or not. You didn’t just march off and try something different. You certainly didn’t just decide to ‘do your bit’ all of your own accord. It wasn’t right. It wasn’t . . . seemly.

‘It’s left us all in a dreadful pickle,’ Florence was saying. ‘Cook’s trying to hire someone new but there’s no one around.’

Now Beth knew the world really had gone topsy-turvy. A matter of weeks ago, any job in service would have been in high demand. As Ma always said, it was a roof over your head, all your meals and a wage. Beth herself might have ended up working in one of the big houses had her sister Sally not got married and stopped working in the shop.

And now even Maitland Hall couldn’t fill Ivy’s position? The world had gone mad.

And I’m just here.

Selling tins of crab to servants from the big houses.

Beth shook her head to clear her thoughts and started entering the purchases into her ledger. ‘Any news from Ralph?’ she asked.

Florence had been stepping out with one of the footmen at Maitland Hall for a couple of years. Enlisting as soon as war was declared, he’d put a ring on Florence’s finger just before he marched away.

‘Got a letter this morning,’ said Florence, starting to pack away the groceries. ‘Thank goodness! I worry like anything when I don’t hear from him. I’ll pick up a few things for him now I’m here and send them on to him.’

‘Where is he now?’ asked Beth. ‘Close enough to send perishables? Because everyone says this ham is wonderful.’

Florence paused, then gave a nervous little laugh. ‘I’m not sure,’ she said.

‘Didn’t he say?’ asked Beth, nonplussed. Surely Ralph would have mentioned where he was and where he was going? Unless he wasn’t allowed.

Florence’s eyes darted around the shop and came to rest on Beth’s face. ‘To be honest, I can’t read most of what he writes,’ she said. Her green eyes brimmed with tears and she dashed them away. ‘I’m so stupid . . .’

Suddenly Beth remembered Florence crying in the school playground, nursing whipped hands for getting her reading or her spellings wrong. ‘Oh, Florence,’ she sighed.

‘Ivy was helping me,’ said Florence. ‘But then she upped and offed and I didn’t know who else to ask. I mean, I’m sure Cook would help, but . . .’

Beth understood. Who would want a dry old stick reading out their love letters? The romantic bits would be bad enough but God forbid there was anything saucy.

‘When’s your afternoon off?’ Beth asked.

‘Tomorrow,’ said Florence. ‘Why?’

‘Tomorrow’s my afternoon off too,’ said Beth. ‘If you haven’t got anything else on, would you like to come here and I’ll read Ralph’s letters to you? That is, if you wouldn’t mind me seeing them.’

Florence paused in her packing and looked up, beaming. ‘I’d like that very much,’ she said. ‘Thank you.’

The door to the shop jangled and both girls looked around. It was Sam, the junior postman, dominating the space with his height, his breadth . . . his manliness. Most of the girls in Woodhampstead were sweet on Sam Harrison – had been ever since they’d all been at school together – and Beth felt herself blushing. It wouldn’t be a delicate flush either; she knew she’d have gone scarlet from her neck to the roots of her hair. There was just something about Sam with his curly dark hair, his deep blue eyes . . . his uniform. The ridiculous thing was that she often saw him several times a day and she knew she blushed every single time.

‘Afternoon, ladies,’ said Sam with his charming lop-sided grin.

‘Afternoon,’ said Beth.

At least she hadn’t stammered.

‘I need a couple of signatures from you,’ said Sam, ‘but I can wait until you’ve finished serving Florence.’

‘Thank you.’ Beth quickly finished parcelling up the last few items. ‘I could write a letter to Ralph from you too, if you’d like?’ she added quietly to Florence. ‘To go with the package you’re planning to send him.’

‘Oh, Beth, would you?’ said Florence, eyes shining. ‘He’s been having a right moan to his Ma that I don’t write to him enough and I haven’t liked to tell her why.’

‘Of course,’ said Beth. ‘Come at half past one tomorrow.’

Florence nodded and left, weighed down with her purchases, and Beth watched the lad who had been sent from the hall jump down from the pony and trap to help her stow her parcels. The jingle of bridles, the swish of wheels through puddles and all was quiet again.

Beth turned to Sam. ‘Hello,’ she said, shyly.

‘Raining cats and dogs out there,’ Sam replied cheerfully. Suddenly Beth couldn’t think of a thing to say.

‘Yes, it’s very inclement, isn’t it?’ she said finally. Inclement?

Inclement!

Who said inclement nowadays?

Sam chuckled. ‘It is,’ he said. ‘Very . . . inclement. Now,

I’ve got a right little haul for you this afternoon. Something tells me that today might be a special day?’

‘Yes,’ said Beth, feeling her blush intensify. ‘It’s our birthday. Mine and Ned’s. Eighteen today.’

‘Well, happy birthday to you both,’ said Sam. ‘And what’s Ned going to be doing now that he’s eighteen?’

‘I don’t know,’ said Beth hurriedly. She didn’t want to discuss what Ned might have decided now he was old enough to sign up. She didn’t even want to think about it. She and Ned had talked about it, of course, but still. She didn’t want to talk about it today. And she certainly didn’t want to talk about it to Sam, who was nineteen but who had a perfectly valid reason for not signing up because he was an only son and his father had died the year before.

‘Of course,’ said Sam, giving her an understanding smile. ‘Well, as l say, I’ve got a right little haul for you both here.’ Beth beamed. She loved the daily post – birthday or no birthday – and she would have loved it even if Sam hadn’t been the one delivering it. The post brought in the exciting, the luxurious, the useful – the things that couldn’t be bought in Woodhampstead. The post brought invitations, gossip and, most importantly, it brought news.

The morning delivery hadn’t contained much of interest but this one more than made up for it. That rectangle would be the nature book she’d ordered for Ned. The smaller one would be the skirt pattern she’d bought for herself. There were several other interesting-looking parcels and a handful of cards for both her and Ned. And – oh, look! – here was a card addressed to her from her cousin Charlotte! Beth would recognise those big forward-slanted letters anywhere – almost falling off the page in their hurry to be somewhere else. She snatched it up and held it to her nose, fancying she could catch a whiff of the heady perfume that Charlotte loved to wear.

Then her eyes met Sam’s and she realised what a clot she must look, standing there clutching a letter to her face and inhaling deeply.

How immature.

How unsophisticated.

How humiliating.

No wonder Sam was laughing.

‘I’m afraid I haven’t got a birthday present for you,’ he said, brandishing another envelope at her, ‘but here’s a little something that stumped the chaps in the sorting office this morning.’

Confused, Beth took the letter from his outstretched hand and resisted the temptation to fan her glowing cheeks with it. Then she realised it was one of those. An envelope with writing so impenetrable, it was almost impossible to decipher. Sam brought them in from time to time – had done ever since he’d come across Beth trying to interpret a shopping list he deemed officially impossible to read. Beth had never failed to deliver the goods.

Yet.

Beth duly studied the envelope, aware of Sam’s deep blue eyes on her. At first nothing made sense. The writing was dense, the up and down strokes exaggerated, and the ink blots and smudges didn’t help. She paused for a minute, waiting to get her eye in, for some clue to the puzzle to emerge . . .

Nothing.

Absolutely nothing.

Just a series of squiggles – apparently too many for a regular address.

Beth was tempted to take out the magnifying glass that Pa used to check that strangers’ coins and notes were genuine, but Sam might think that was cheating. Maybe she should at least open the hinged counter and go over to the shop window for some proper light? That wouldn’t be cheating, but it would leave her without the safety of a barrier between her and Sam. She was only wearing her second-best skirt that day and the hem was a little ragged on one side . . .

Oh, for goodness’ sake, Beth.

Concentrate.

Still nothing. Was she going to have to admit defeat?

Ahh . . . but she’d already given herself the clue.

Too many lines for a normal address.

The writer was one of those who split words randomly onto two lines.Yes, there it was: Woodha on one line, mpstead on the next. And then Hertfo on one line and rdshire on the following. Not even a logical break in the words – but at least it gave her something to go on. And – aha! – it was obviously an elderly writer because she or he was using the old long ‘s’, which looked more like a ‘f’’ in the double-s words. Mrs McBride used it sometimes and it made molasses look like molafses. And – yes, again! – they were using the old letter ‘c’, which looked more like a capital ‘e’ with its elongated tail.

Beth looked up and smiled at Sam. ‘Jessica Carter, Baronsmead, Nomansland, Woodhampstead, Hertfordshire,’ she rattled off triumphantly.

Sam slapped his hand against his thigh. ‘You’ve done it!’ he said. ‘You’re a marvel, you really are. And it’s close enough that I can just drop it off now. You really should join the post office – you’re wasted in here!’

Beth laughed. She loved it when Sam teased her and his eyes went all crinkly at the corners. ‘Lugging those great big bags around in all weathers?’ she said. ‘I have enough trouble with the tea and the flour here, thank you. And I burn some- thing rotten in the sun.’

The door jangled behind Sam and a couple of women came in, chatting intently.

‘Well, goodbye then,’ said Sam. And he was gone.

The rest of the afternoon was busy.

Really busy.

It seemed that the whole of Woodhampstead had left it until four o’clock on Wednesday afternoon to go shopping which, to be honest, they probably had because the rain was finally letting up and a pale April sun was trying to peek through the clouds.

In they came, gently steaming from the rain, chatting about the weather and over-buying just about everything that happened to be in stock. Mrs McBride came back to complain the butter had been too salt but she would take another half a pound anyway. Mrs Lovell needed condensed milk – as much as possible – to make coconut pyramids for the village fete that weekend. Mrs Collins wanted to tell her, in great detail, about her cousin’s friend’s neighbour who had just lost a leg in France. Beth didn’t mind the crowds, didn’t mind the gossip; it made the day go faster, and took her mind off what Ned might or might not have decided to do. But where the dickens was Ma? Ma always worked in the shop in the afternoon with Beth but she had taken off some- where and Beth had no idea where she’d gone. And on her birthday to boot!

By five o’clock, the crowds of shoppers had dwindled away and Beth was exhausted. She lifted up the hinged counter and walked across to the door, flipping the shop sign from ‘open’ to ‘closed’.

Drained, she leant her head against the glass and stared out across the street. The view hadn’t changed since, well, ever. The rain had started up again and was bouncing off the dirt road and dripping from the eaves of the cottages opposite. Even from here, and with the door closed, Beth fancied she could smell the heady scent of the sweet peas in their front gardens. School had finished for the day and children had filled the streets as they did every day, rain or shine, winter or summer – their homes too small to stay cooped up indoors. The boys were playing football and the girls had formed a long line across the road and were playing a complicated game of catch, which Beth remembered from her own childhood. Everything looked as it had always looked. Pretty soon, Pa would arrive home and Mayfair, the lovely old mare who pulled the delivery cart, would take a deep draught from the trough outside. Pa would wave to her and then lead Mayfair through the arch beside the shop and into the stable behind and then old Mr Hiscock would arrive with his ladder and the paraffin oil to light the street lamp and another evening would begin . . .

And yet, despite the gentle rhythms and routines that had punctuated her eighteen years, below the surface, everything had changed.

Most of the young men had gone.

Her older sister Sally’s husband Bertie. His brother Reginald. Florence’s fiancé Ralph. Farm labourers, gravel- diggers, gardeners, coal merchants, brick-layers, railway porters, errand boys . . . the small town had lost them all. Almost two hundred of them. Less than a week after war was declared, they’d been swallowed up by the Beds, the Royal Engineers, the Army Service Corps, the Labour Corps, the Egyptian Expeditionary Force and goodness knew what else and marched off to an uncertain future. Some had died. And throughout the year, more and more boys had turned eighteen and signed up.

And here was Ned, squelching up the street, shoulders hunched, hands in pockets, sandy hair forming little peaks in the rain. To an outside observer, there would have been nothing unusual in the way he pushed the door open, said hello to Beth and disappeared through the counter into the storeroom and the house beyond. But, to Beth, everything was different. It was what Ned hadn’t done. He hadn’t made a silly face. He hadn’t attempted to ruffle her hair or to pull her plait. He hadn’t even tried to filch a piece of ham or a sliver of cheese.

Beth sighed deeply and looked around at the rows of colourful tins and shining jars on the wooden shelves. The shop, as usual, was immaculate. But, beneath the surface, things were shifting beyond recognition.

I’m eighteen years old today and everything is changing.

Did you enjoy this free extract? Pre-Order The Post Office Girls here.

Publishing in ebook on 29th April 2021 and paperback and audiobook on 13th May 2021.