Fair Play: is your to-do list endless?

In Fair Play by Eve Rodsky, she urges women to evaluate the distribution of responsibilities in their families and relationships. Chosen as a Reese Witherspoon Book Club pick, Fair Play seeks to show you that there is a way to share the mental load, rebalance your relationship and transform your life. In this extract from the book, Eve explores the dilemma of never ending to-do lists.

WHY CAN’T WE EVER SEEM TO GET AHEAD OF OUR TO-DO LISTS?

The more I talked with my girlfriends who’d entered motherhood, I realized we were all having trouble getting it all done— and what’s more, we were all having trouble identifying exactly what it was we were doing. Why were we all so busy?

It turns out this phenomenon has a name—many names, actually. One of the most popular is “invisible work”: invisible because it may be unseen and unrecognized by our partners, and also because those of us who do it may not count or even acknowledge it as work . . . despite the fact that it costs us real time and significant mental and physical effort with no sick days or benefits. No doubt you, too, have read articles describing this “mental load,” “second shift,” and the “emotional labor” that falls disproportionately on women, along with the toll this domestic work takes on our lives more broadly.

But what are we really talking about here? Sociologists Arlene Kaplan Daniels and Arlie Hochschild started giving us the language to talk about these deeply felt (but largely unarticulated) inequities in the 1980s, and since then, plenty of intelligent women have advanced the conversation and the popular vernacular.

Mental Load: The never-ending mental to-do list you keep for all your family tasks. Though not as heavy as a bag of rocks, the constant details banging around in your mind nonetheless weigh you down. Mental “overload” creates stress, fatigue, and often forgetfulness. Where did I put the damn car keys?

Second Shift: This is the domestic work you do long before you go to work and often even longer after you get home from the office. It’s an unpaid shift that starts early and goes late, and you can’t afford to lose it. Every day’s a double shift when you have two kids’ lunches to prep!

Emotional Labor: This term has evolved organically in pop culture to include the “maintaining relationships” and “managing emotions” work like calling your inlaws, sending thank-you notes, buying teacher gifts, and soothing meltdowns in Target. This work of caring can be some of the most exhausting labor (akin to the day your child was born), but providing middle-of-the-night comfort is what makes you a wonderful and dependable parent. It’s OK, Mama’s here.

Invisible Work: This is the behind-the-scenes stuff that keeps a home and family running smoothly, although it’s hardly noticed and is rarely valued. The toothpaste never runs out. You’re welcome. In an effort to “physicalize” this heavy burden carried by women yesterday and today, I began collecting every article I could find on the subject of domestic inequality. After amassing 250 articles (and counting) from newspapers, magazines, and online sources, it was disturbing to recognize that, since women began writing about this in the 1940s, we haven’t made enough progress in sharing the burden with our partners or finding an answer to this problem that men could buy into. Same sh*t, different decade.

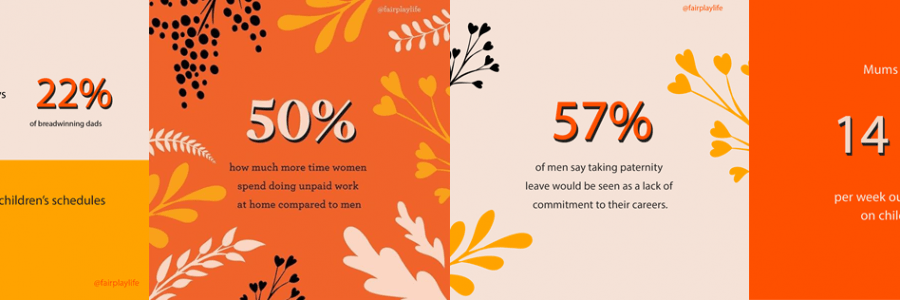

According to the most contemporary research, women still do the bulk of childcare and domestic work, even in two-earner families in which both parents work full-time and sometimes even when the mother earns more than her partner. As if reflecting a mirror onto my life, I stumbled upon another study revealing that men who stood up for their fair share of housework prior to having kids significantly cut back their contributions after kids—by up to five hours a week.

Wow, even the good guys?

As I considered the vast research and literature, past and present, bravely naming and articulating this problem, I thought: OK, we know there’s an imbalance. But where is the manual with a practical and sustainable solution? Sure, it’s helpful to understand the breadth of the condition and its historic underpinnings, and it felt gratifying to know that I was not alone in this predicament and that plenty of women had been fed up and writing about it for decades. But what can we do to change it? I became determined to find out.